February 11 marks UNESCO’s International Day of Women and Girls in Science, a day to advocate for education and career opportunities for women as global scientists, technology innovators, and inventors.

Among those to celebrate are women scientists who are also Toastmasters. These women emphatically stress the need for communication skills in their work, whether interacting with the public, CEOs, financiers, policy makers, students, or their own professional peers.

Here are some of their stories in the first installment of this two-part series.

Soukaina Bennaamane

Bennaamane, who recently received her doctorate in chemistry at Université Toulouse 111-Paul Sabatier, had just joined Toulouse Toastmasters Communication, in Toulouse, France, when her fellow club members encouraged her to enter a regional speech contest.

She hadn’t yet given a club speech, a core activity in Toastmasters training. However, she entered and discovered something important about herself: “It was very challenging, but I learned I can do things I didn’t think I could,” she says. “Before Toastmasters, it was difficult for me to clearly explain my research because it’s very complex,” she adds. “Now I can organize my ideas and explain them easily. That’s due to the incredibly insightful feedback I receive from the club.”

Effective communication is critical to scientific success, she adds. “Communication is the clue to progress and being able to convince others that research can impact our society for good. Moreover, to advocate for science—to publish in a respected journal or apply for program funding or implementation—the scientist must be a strong, confident communicator.”

Photo Credit: Karla Gowlett

Photo Credit: Karla GowlettLucy Rogers

In 2013, Rogers joined the Bicester Achievers Toastmasters Club in Bicester, England, and Online Orators, a virtual club based in England. The engineering professor had just taken a stark self-assessment of her speaking skills. “I was giving electronics lectures to students and boring myself, let alone the poor students,” she remembers.

Rogers is a Visiting Professor of Engineering: Communication and Creativity at Brunel University in London. She refers to herself as “an inventor with a sense of fun.” She credits Toastmasters training, particularly Table Topics® and practicing speeches in front of her club, for boosting her speaking skills, especially as she loves to produce science videos. “I do a lot of cross-disciplinary work so when I’m speaking before the club, they let me know if there’s a term they don’t understand. That’s also helped me teach other engineers how to improve their presentations,” she says.

Rogers echoes her follow scientists on communicating science to the public. People with non-science backgrounds hear things differently than those with technical training, she explains.

“For example, theory means guess or hunch to the public, but to scientists, it means an explanation backed by experiment and testing. Uncertainty means ignorance to the public, but in science it means range. So messages can get confused,” she notes.

“Sadly, in my eyes, the people who make decisions and hold the purse strings often do not have science backgrounds. Therefore, it’s up to scientists and engineers to make themselves understood,” Rogers says.

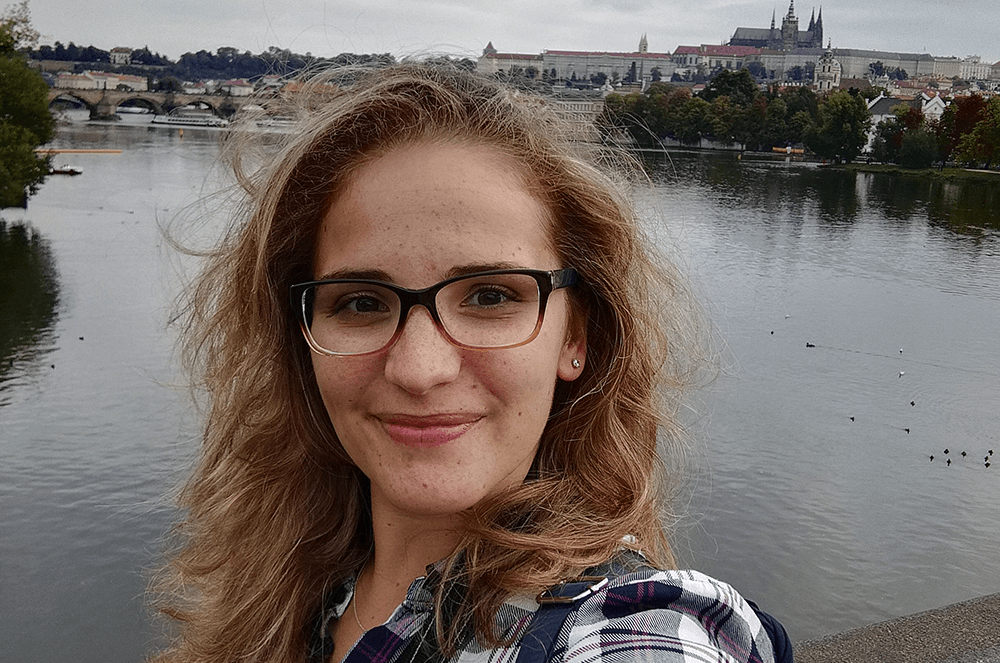

Joana Campos

As a child, Campos loved “fixing things around the house.” That led her to engineering studies, coupled with biology and chemistry. She is now a doctoral candidate in biotechnology at Lund University in Lund, Sweden.

“I fell in love with microorganisms and what they can do for us,” she says. “People usually look at microbes as bad little things that cause disease. My goal is to show they can produce chemicals that can make our lives better.”

Turning such research into reality means earning the support of decision-makers. “I’ve often presented my work at scientific conferences and in meetings with CEOs—and while they are more prepared to understand my research, I still have to be careful not to make them fall asleep in my presentations! Scientific work can become very tedious if you don’t have good pitching talents—like a salesperson who wants to sell the audience on the biggest improvement to their lives.

“The company CEO is the toughest—they are concerned with cost and want a brief and assertive scientist to deliver trustworthy information. In science, there are so many variables that you are never 100% certain if you’ve sold your research, so you have to be trained to look like you are,” she explains.

Toastmasters, Campos says, “serves exactly these capabilities—to learn and practice the best way to deliver a message efficiently, briefly, and with confidence.” She is a member of both Fabulastic Women in Toastmasters and Toastmasters@Ideon, a science park located next to Lund University.

Sabrya Carim

Cell biologist Carim, a Toastmaster in the CN Collaborators Club in Montreal, Canada, continually melds her communication capabilities with her cancer research.

“To better understand what goes wrong in cancer (a result of uncontrolled cell division), Toastmasters has taught me the power of storytelling, and to use voice modulation and gestures to enhance my presentation delivery and hence, more strongly convey my message,” she explains.

“By training, I was used to delivering (and hearing) science presentations delivered at a uniform pace and in a monotone. That’s fine if the audience is hearing clear, convincing information,” she says.

However, Toastmasters has taught her to “liven up my presentations by varying my voice and changing the speaking pace. I’ve learned to explain my speech as a story, with a clear opening, introduction, and small anecdotes to drive home conclusions. I end with a call to action which, for me, is the importance of continuing to fund research into cell division.”

She’s also applied Toastmasters leadership skills—active listening, organizing, delegating, planning—to assist her boss, a busy professor, in managing his lab. “Toastmasters is truly a great find and I highly recommend it to everyone. I recommended it to my boss!”

Cyrielle Chappuis

Chappuis, a doctoral candidate at the University of Geneva, Switzerland, joined the International Geneva Toastmasters Club with a very specific goal.

“I wanted to become more assertive and clear in meetings, or when debating research work," she notes. Since her studies focus on social cognition and voice, speaking skills help inform her research. “Voice is a communication tool,” she says. “It evolved serving a social purpose.”

Chappuis purposely chose the “persuasive influence” curriculum in Toastmasters' Pathways education program. “It focuses on negotiating positive outcomes by improving interpersonal communication and public speaking skills. I’m convinced that a good part of clear communication in any setting relies on skills such as empathy and conflict management.”

Chappuis applauds the world’s skyrocketing attention to science and technology.

“The thirst for scientific knowledge is very encouraging; I’m convinced that a more educated society is the key to progress,” she says.

“However, this interest also comes with the risk to misunderstand or miscommunicate findings or methodology. Science can lead to progress only if it’s applied correctly. Popularizing results while keeping an accurate and critical stance is a balancing act worth learning.”

Chappuis sees science as a core communicative community, which is what Toastmasters teaches. “Scientists can’t work alone—they have to collaborate effectively with policymakers, politicians, stakeholders, and others. That ability creates interest in the science and results in prolific collaborations."

Rashmi Ketha

In 2018, Ketha joined Parsippany Toastmasters Club in Ledgewood, New Jersey, when she started a full-time position in data science, with a focus on artificial intelligence and machine learning. “I knew Toastmasters would give me a chance to grow in a new space and bring those skills to my professional world,” she explains.

Among her favorite newly polished skills: the art of active listening. “I learned the importance of speaking at the right times and when to remain silent and really listen to another speaker,” she says.

Speaking is also critical for a scientific investigator. “Data science is also an art—the art of engaging listeners. That’s integral to being seen, heard, and therefore, successful,” Ketha says. Imparting understandable facts is crucial, she adds.

“With the increasing influence of social media and news media, it’s imperative to have a communicative presence, supporting the right data, to be credible in the scientific field,” she explains.

After a few months as a Toastmaster, Ketha gained the confidence to host a two-hour presentation at her company, directed at women working in data science. “We shared key data points, our technical ideas—and had plenty of time to network with like-minded thought leaders," she noted.

What does she think is Toastmasters' most undeniable benefit? “I learned that the art of effective oration amplifies the message. Toastmasters helps you use your voice and convey that message to the right audience.”

Stephanie Darling is a former senior editor of and frequent contributor to the Toastmaster magazine.

Related Articles

Communication

Women in Toastmasters Talk Science

Communication

The Importance of Being Scientifically Literate

Presentation Skills

Previous

Previous

Previous Article

Previous Article