“Words—so innocent and powerless as they are, as standing in a dictionary, how potent for good and evil they become in the hands of one who knows how to combine them.”

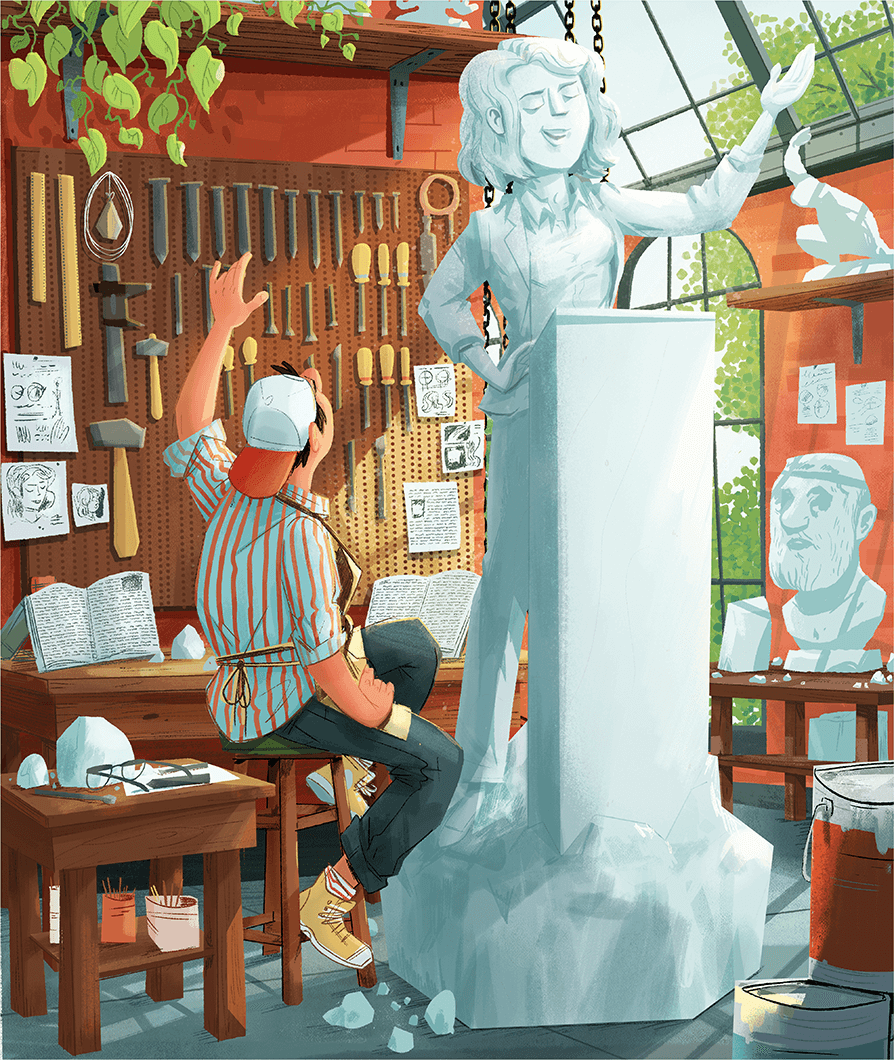

—Nathaniel HawthorneMore than 500 years ago, Michelangelo stood before a slab of marble. In his mind, he saw the image of what was sleeping inside the stone. It was his job to select the tools he needed to set free the figure he envisioned.

Renaissance-era measuring sticks, plumb bobs, and calipers followed by mallets, chisels, files, and rasps—all took their turn in his hands. Using these devices, he carved the marble into a graceful statue, “Kneeling Angel,” that has enthralled audiences for centuries.

To build something that will stand, an artist must know his tools. The same is true for speakers and writers.

If you don’t know your way around the assortment of language devices that will wake up your voice, it’s time to discover your substantial, significant, and seriously awesome tools of the trade.

You Have Two Sets of Tools.

Let’s begin by exploring the differences between rhetorical and literary devices. Rhetoric has historically leaned toward the realm of public speaking. Literary devices, as the name suggests, have been used mostly by writers. It’s not a perfect split; several devices fall into both categories. For example, metaphor is used by both speakers and writers. But here’s what you should know about the general difference:

Rhetorical devices help a speaker express feelings about a subject using articulate persuasion, while literary devices help a writer to tell a story with eloquence.

Rhetoric helps a speaker shape ideas so they appeal to audiences’ sense of logic, emotions, ethics, or passing of time. These four methods, called logos, pathos, ethos, and kairos, were long ago determined to be the best way to influence the listeners’ decision-making process, which usually involves the brain, heart, morals, or feeling that the person is running out of time.

Writers commonly use literary devices to add artistry—color and flair—to their works. While they may be tasked with convincing someone to do something (perhaps read to the next page), the overall effectiveness of a literary device is not measured by its ability to advance an argument. Rather, it’s in how beautiful and graceful it makes the writer’s expression.

Of course, if you’ve given a club speech, no doubt you’ve already worked hard to catch your listeners’ attention with elegant use of spoken language. What’s more, you’ve probably tried, at least once, to convince someone to do something by writing an email or sending a letter. With social media marketing being an absolute must for most businesses and organizations, today’s speakers spend a lot of time writing. By the same token, writers must be able to verbally present and discuss their written works. So yes, definitely some of the tools are useful for both kinds of communication. Still, it helps to understand why the two sets of devices were originally conceived, because the more you understand their original purposes, the more you can use them effectively in today’s world of mass communication.

Peculiar Words. Simple Ideas. Powerful Effects.

Because of their Greek or Latin origins, a lot of the devices have strange-looking names like aposiopesis, epizeuxis, onomatopoeia, synecdoche—words that could make the most brilliant professor’s head spin. But don’t give up. In many cases, learning to use a rhetorical device is not as hard as pronouncing its name. In fact, playing with these cool tools can be fun. Let’s try one here:

tmesis [tuh-mee-sis]

You’ve probably done this many times without knowing what it’s called. When you split open a word or phrase and insert another word or phrase inside for emphasis, that’s tmesis! It’s a great technique to add a quick laugh while emphasizing a point.

Example from Pygmalion by George Bernard Shaw:

Eliza Doolittle says, “abso-blooming-lutely.”

Example from Toastmasters:

Today’s speeches were wait for it SO AWESOME!

Example from my author bio:

Written by Beth that magnificent writer Black.

Example from Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare:

Juliet says, “This is not Romeo; he is some other where.”

TIP: When concocting your own tmesis, be sure to pick the right spot to split the outside word. Try to create a nice rhythm with the inserted word. If Shaw, for example, had given Eliza the word, “ab-blooming-solutely” or “absolute-blooming-ly,” it would not have worked. Think of this as an opportunity to play with words until you get the sound you truly woo-hoo love.

Let’s try another one, this time with a really odd name:

hendiadys [hen-dī-uh-dis]

If you’ve ever heard a couple pronounced “husband and wife,” then you know hendiadys. In traditional rhetoric, this tool links two nouns with “and” to express a single idea. In today’s modern usage, we don’t limit ourselves to nouns. You could say “listen and learn,” combining two verbs. This form is usually slower to say than a noun plus its modifier, such as “nice and warm” instead of “nicely warm.” As with many such tools, it adds emphasis when you slow down slightly to say the longer version.

Example (nouns): hearth and home

Example (verbs): rest and recuperate

Example (adjectives): sweet and sour

TIP: Use this when you want to equalize two parts of a message. Telling someone to try and sleep is more balanced than simply ordering them to go to sleep. This polite form may make the speaker appear more kindhearted by bringing the word “try” to an equal level with “sleep.” Hendiadys balances the two words, making it a little gentler than saying, “Go to sleep,” or even, “Try sleeping.”

How It’s Done.

An example of hendiadys adds humor in the 1980 film The Blues Brothers. Here, actors Dan Aykroyd (as Elwood) and Sheilah Wells (as Claire) make a play on the locally favored music:

Elwood: What kind of music do you usually have here?

Claire: Oh, we got both kinds. We got country and western.

The joke works, because “country western” is one type of musical style, and Claire is emphasizing that they have both halves of the whole.

Here’s one more device:

anaphora [uh-naf-er-uh]

This device relies on repetition of the first part of a sentence to build substance and significance. A recent speech at the United Nations used this technique effectively:

“When women participate in peace processes, they are more likely to last. When women work, the economy grows faster. When girls are educated, their families are healthier. And yet, women still face huge hurdles that prevent them from harnessing their potential, and their communities from reaping the benefits.”

María Fernanda Espinosa Garcés, president of the 73rd session of the U.N. General Assembly, addressing the Women’s International Forum in 2019By building up to her main point, Ms. Espinosa amplified the significance of what happens when women are empowered. Without the anaphora poetically building her case for women, the description of hurdles that followed would have been less meaningful.

Look around and listen. Rhetorical and literary devices are everywhere. They add rhythm and poetry that amplify the ideas shared by speakers and writers.

You may have noticed several examples of alliteration—repeating the first letters in a string of words—throughout this article. I hope this device made the article more memorable and quotable. When you practice using these tools, you’ll develop eloquence, fluency, and poise while unleashing your passion and wit through better delivery than ever before. Like Michelangelo standing before his marble, you will stand before your audience and prove that you are a master of your art.

Beth Black is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Orange County, California. Learn more about her at PracticalPoet.com.

Previous

Previous

A Fun Way Of Talking, Yoda Has

A Fun Way Of Talking, Yoda Has

Previous Article

Previous Article